City Re-Invests in Hospital-Based Violence Intervention

Published on October 31, 2023

By Kayla Chadwick-Schultz

City Speaks subscribers had exclusive access to this article one week ago. You can too! Sign up to receive a bi-weekly newsletter that connects you to what’s going on in Charlotte government.

Being a teenager is hard enough on its own, but being a teenage victim of violence comes with unique challenges that can’t be solved alone. So, when a 17-year-old Charlotte resident arrived at Carolinas Medical Center with a spinal cord injury after being shot, he was fortunate to meet Britney Brown, Coordinator of Atrium Health’s Violence Intervention Program. Brown and her fellow intervention specialists remained connected to the young man throughout his physical therapy. Eventually, he trusted them enough to reveal that he did not want to leave the hospital. Leaving the hospital meant going home.

This fear of returning home or returning to a situation that landed you in the hospital in the first place is common among victims of violence. The Violence Intervention Program staff knows that, and they know what to do when someone expresses this concern to them. “We designed the program for us to set up scheduled times where we could meet him in the community, and he could just spend time outside of his home,” Brown explained. “It’s really helped him build his confidence back up and want to be back in the community.”

Without the intervention of this life-altering program, there is no telling where this young man may have ended up. His story is one of many successes that Atrium Health’s Violence Intervention Program has generated since its 2022 launch, and it’s why the City of Charlotte renewed its investment in the program with the adoption of the Fiscal Year 2024 budget.

Understanding the City’s Investment

Fiscal Year 2024 began back on July 1, 2023, and with it came a new wave of publicly funded programs and initiatives. The continuation of the city’s partnership with Atrium Health’s hospital-based Violence Intervention Program, however, is just one example of an old initiative made new again with the support of city finances—$250,000 worth of city finances, to be exact.

City Manager Marcus Jones speaking during a 2021 press event announcing the city's Atrium Health partnership.

The allocated amount is a small fraction of this year’s $5 million budget for the Corridors of Opportunity initiative, which is the city’s commitment to creating safe and prosperous communities for residents to build legacies for future generations. The word “safe” is key here. Not only does it highlight how the hospital-based Violence Intervention Program fits within the Corridors of Opportunity initiative, but it also emphasizes the need to put public safety first. Communities cannot prosper if they are not safe, and residents do not feel safe when violence is so prevalent that it becomes a familiar part of everyday life. Placing a budgetary emphasis on public safety through SAFE Charlotte is an investment in Charlotte’s future and the success of its residents. Additionally, Atrium Health will match the city’s $250,000 contribution to increase this year’s total funding for the program to $500,000.

Violence Intervention in Action

In collaboration with the City of Charlotte, Atrium Health’s Violence Intervention Program officially launched in 2022, making Charlotte one of 40 U.S. cities with a hospital-based program. This multidisciplinary program—combining the efforts of medical staff with trusted community-based partners—pairs victims of violence aged 15 to 24 who enter Atrium’s Level 1 Trauma Unit in Carolinas Medical Center with wraparound services to help prevent them from becoming future perpetrators or repeat victims of violence. In other words, the program aims to break the cycle of violence that often materializes as a result of an initial incident.

Atrium Health first noticed the cyclical nature of violence within the region during a study it published in the Journal of Surgical Research. The study, which investigated admissions and readmissions among 1,215 patients with violence-related injuries between 2009 and 2015, revealed that 1 in 4 victims of violence returned to the hospital within 21 to 31 months of their initial admission. 14% of these readmitted patients returned due to incidents of life-threatening self-harm, emphasizing the need for extended psychological care in addition to physical rehabilitation.

Motivated by the results of the study, Atrium developed a plan to prevent hospital readmissions for victims of violence. This required looking beyond the more obvious causes violence, such as access to firearms, and starting to address social determinants of health—defined as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The program Atrium ultimately designed needed to assess these conditions in addition to a patient’s injuries. Once assessed, staff could connect patients with productive community resources.

Aerial view of Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center.

It works like this… When victims of violence arrive at Carolinas Medical Center, members of the hospital staff first assess the nature of the injury. Participation in the program requires the treatment of a non-accidental gunshot wound, stab wound, or blunt assault-related injury. This does not include injuries that are self-inflicted, related to human trafficking, or the result of domestic violence; the hospital has separate programs designated for those circumstances. Once the hospital determines eligibility for the Violence Intervention Program, staff members “want to make pretty immediate contact,” said Brown. “We also want to make contact with any family or friends that may be supporting them.” It’s important for the staff to make this contact and begin building relationships as early as possible, because the next step is crucial. It's a conversation.

Brown continued, “We sit down and have a conversation with them to determine how we can support them. We have a social determinants of health interview that will figure out what information we can carry on with us and connect them with community organizations that can serve them as they leave the hospital.”

The staff tries to keep the social determinants of health interview short and sweet. It often includes questions about their safety, particularly how safe they feel in their homes and communities, and other major necessities: food, utilities, education, etc. A patient’s answer to these questions provides the staff with enough insight to figure out how to support them moving forward.

The Public Health Approach

This hospital-based program is all about filling the gaps in a person’s life that may make them more susceptible to violence. It does not possess a political agenda or focus on any singular type of violence, such as gun violence. Instead, the program treats violence like a disease.

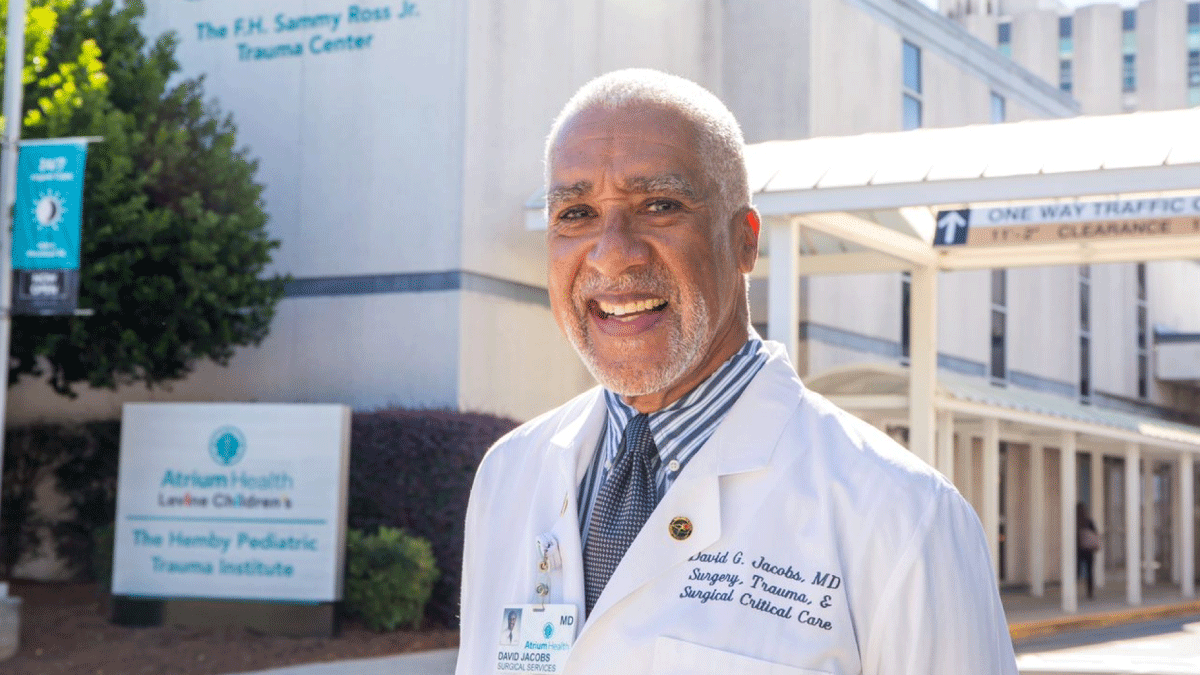

As Dr. David Jacobs, Medical Director of the Violence Intervention Program, explained, “If you think about the public health approach to violence, and you think about violence as a disease, the cause of the disease are those social determinants of health. The poverty. The lack of education. The lack of housing and food and all those kinds of things. That’s the cause. When you start talking about guns, and you start talking about the media, and you start talking about gangs, you’re talking about the symptoms of a disease.”

Dr. David Jacobs, Medical Director of the Violence Intervention Program.

As with any disease, it’s important to treat the cause rather than the symptoms, which is why Dr. Jacobs advocates for a long-term management approach to violence intervention. However, hospital stays are not always for long periods of time. For example, a stab wound to the arm would not warrant the same length of care as a gunshot wound to the abdomen. So, why start this long-term management at a hospital?

“We believe that getting shot, getting stabbed, getting beat up so severely that you end up in a trauma center can be a moment of reflection for our patients,” said Dr. Jacobs. “One of the goals of the program is for us to have a very pointed, direct conversation with our patients or clients and say, ‘Are there some decisions that you’ve made that are going to keep you going down the wrong road? And what will happen if you continue to make the decisions that you’ve been making?’ Here’s the opportunity.”

In other words, the Violence Intervention Program meets people where they are: at one of the lowest points of their lives. This gives violence intervention specialists a unique opportunity to connect people who are ready to make a change with the necessary change-making services. From there, the continued support of the Violence Intervention Program team, even long after they leave the hospital, results in the long-term management that Dr. Jacobs prescribes.

2023 and Beyond

The City of Charlotte has a number of violence prevention measures in place, but its continued investment in Atrium Health’s Violence Intervention Program is an essential part of the bigger picture: a safer Charlotte. And that safer Charlotte includes everyone, regardless of their address.

Brown described the biggest commonality between most program patients as a sense of inevitability, with most saying things like “I knew this was going to happen. This is the area I live in. This is the community I live in. I’ve seen this my whole life. It was only a matter of time before this happened to me.” By addressing the social determinants of health that contribute to this hopelessness, Atrium’s partnership with the City of Charlotte extends beyond the individual and into our communities. If we can continue to fight the cause of the disease, we can get one step closer to curing it in our city.