More than Just a Book: Charlotte's History in the Green Book

Published on February 13, 2025

A postcard of the Hotel Alexander. (UNC Charlotte Atkins Special Collections)

By Morgan Newell

Picture this: you're set to embark on a vacation you've been planning for months. The car is full of gas and the trunk packed with your suitcases. You set off with your trusty guidebook to the city you plan to visit. In it, there might be sites to see, restaurants to eat at, and tourist attractions you cannot miss.

When you think about this guidebook, you probably wouldn’t describe it as lifesaving. Helpful or maybe even convenient, but not lifesaving. However, that’s exactly what the Negro Motorist Green Book was to Black Americans traveling across the country in pre-Civil Rights Movement years.

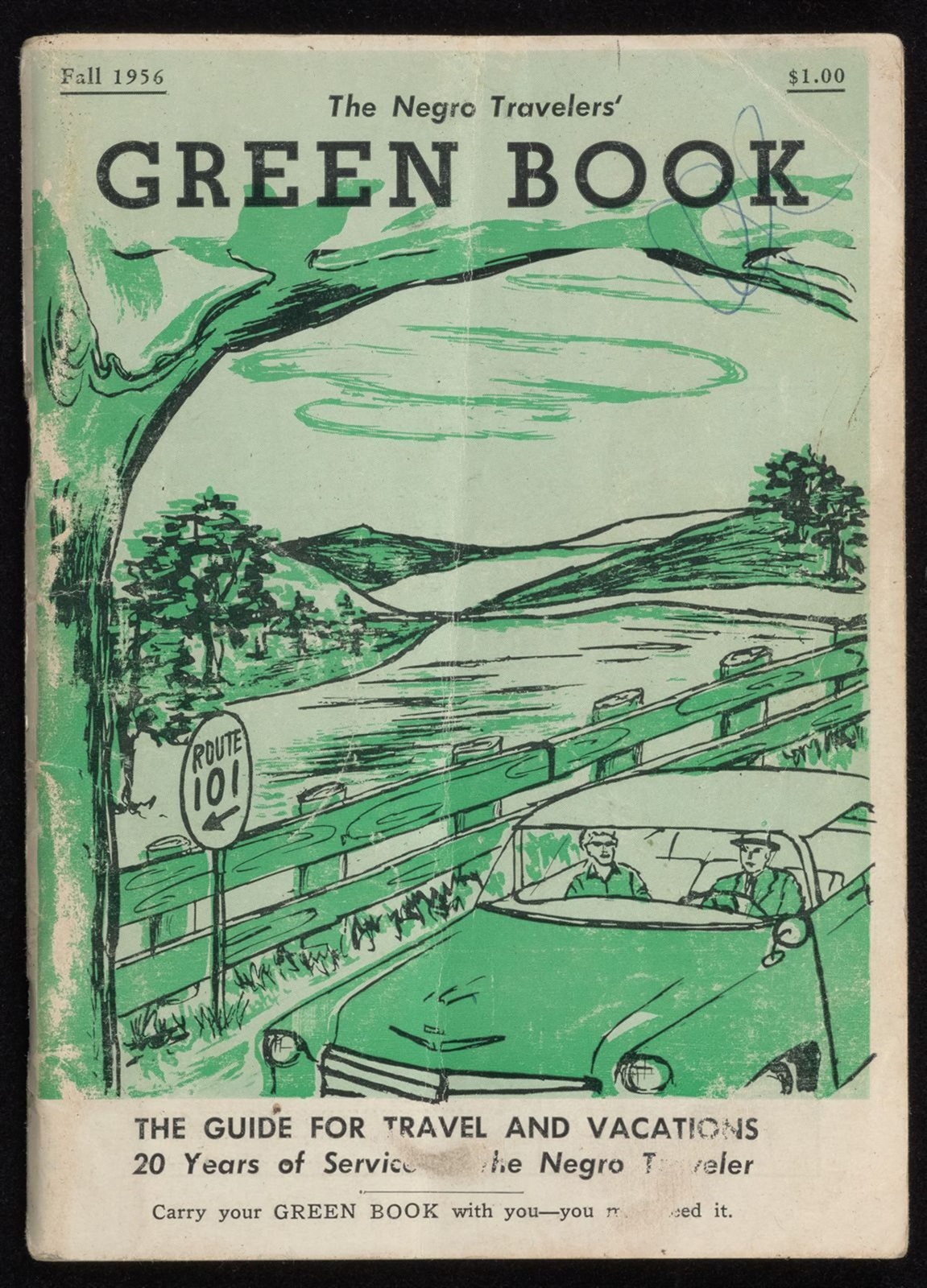

The front page of the 1956 "The Negro Travelers' Green Book." (New York Public Library Digital Collection)

"The Negro Motorist Green Book," or Green Book for short, was a guide filled with businesses that accepted Black people in a segregated America. The first edition, published in 1936, started in New York City. It featured Black-owned businesses in Harlem and was so successful that the need for a nationwide Green Book quickly became apparent. Two years later, the Green Book expanded to include 22 states. That expansion featured two Charlotte businesses—the Charlomac and Sanders hotels.

“The Green Book was almost like the Bible for families that wanted to travel,” said Mecklenburg County Commissioner Arthur Griffin. “Really, it was a bible for anyone who wanted to know the safe places you could go.”

Born and raised in Charlotte, Mecklenburg County Commissioner Arthur Griffin spent most of his years on 6th Street in the First Ward. Griffin remembers walking to school. He delivered the Charlotte News in the afternoons. He got his first hair cut on East 7th Street. What he also remembers is living in what he calls a segregated Charlotte.

Mecklenburg County Commissioner Arthur Griffin. (Commissioner Arthur Griffin)

“People talk about the colored water fountains, but I actually used them,” he said. “I was one of the people turned away from certain establishments because of the color of my skin.”

Griffin says segregation made Black businesses and the Green Book even more important. The guide was full of restaurants, hotels, drug stores, garages, and even gas stations. These places were not just businesses, but lifelines.

“The downside of the Green Book is it was necessary,” Griffin said. “Because at that time in history, knowing the safe places to go was a matter of life or death.”

Even though Griffin didn’t travel often, he lived down the street and within walking distance to some of the Green Book locations. He recalls eating at Chicken & Ribs and partying at Excelsior Club as a teenager. He would spend his paper route money on ice creams at the Igloo Bar. What memories stick with him the most was watching the fanfare at the Hotel Alexander right down the street from his house.

A picture of the Hotel Alexander. (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library)

“Growing up, you would see and know important African Americans were going into the Alexander hotel because it’s where all the Black celebrities stayed,” he said. “You knew they were important because they were staying there, but it took me growing up to realize how important, especially for us.”

Between 1938 and 1966, the Green Book featured 55 Mecklenburg County businesses. Today, only three of the original buildings still stand: Chicken & Ribs, the Igloo Bar, and Excelsior Club. Chicken & Ribs is the only Mecklenburg County Green Book business still up and running. The Excelsior Club is still standing, but needs someone to help preserve it.

Many of the buildings were lost to urban renewal—a process of redeveloping urban areas that often led to the displacement of entire communities. In Charlotte, those communities were mostly Black. For example, the Biddleville and Varsity Luncheonettes once stood on 1118 Beatties Ford Road. The 500 block of McDowell Street was the center of Brooklyn Village, made up of different businesses like J. C. Sandwich Shop and McDowell’s Barbershop. Black-owned restaurants, stores, and hotels peppered the city from Oaklawn Avenue to Caldwell Street. These buildings were torn down in the 1960s and 1970s, and the land was used for different purposes over the years.

“When you grow up, you think about the buildings, stores, and community you left many years ago and there’s a twinkle in your eye when you see the building, stores, or community again,” Griffin said. “Most of these institutions we are talking about have been torn down. There’s a degree of sadness that we’ve lost these places and can’t show our grandkids or great grandkids.”

500 Block of S. McDowell Street in the 1960s. (Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library)

While the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission has researched street addresses for most of the city’s Green Book businesses, Griffin feels there wasn’t enough done to honor these places once hailed as safe havens. There are no historic markers or designations to look back on. However, the county commissioner says we can still honor these establishments for the impact they made in the Charlotte Black community and beyond.

“You cannot go forward unless you look backward,” Griffin said. “That’s a prerequisite of progress, because you won’t know how far you’ve progressed until you look backward. History is important to ground yourself with where you’ve been to figure out where you’re going.”

The City of Charlotte recognizes this importance and is committed to honoring and uplifting our Black history. When urban renewal displaced Black communities in the 1960s, many people were pushed into new areas of the city. While the Green Book locations were lost in the process, Black business owners started to rebuild in their new homes. However, these neighborhoods, largely went underinvested for years. Now, thanks to the Corridors of Opportunity program, the city supports these areas with community-driven goals and initiatives. A multi-million dollar investment into Corridors of Opportunity funds transportation, affordable housing, and business development projects. While there is still work to be done, these investments are helping to move our city forward and build lasting legacies of which residents can be proud.

You can help shape historic preservation in the Beatties Ford/Rozzelles Ferry Corridor. The City of Charlotte is currently developing the neighborhood’s Corridor of Opportunity Playbook and needs your feedback to ensure future investments reflect the values, needs, and priorities of the community. Take the survey by Feb. 20 to shape the priorities.

If you would like to learn more about The Negro Motorist Green Book, visit the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission’s website. If you’d like to see the Green Book throughout the years, visit the New York Public Library Digital Collections.