Charlotte Pride: Charlotte LGBTQ+ History Timeline

Published on August 16, 2023

By Kayla Chadwick-Schultz

In honor of Charlotte Pride returning to Uptown this August for its annual festival and parade, the City of Charlotte is reflecting on 60+ years of recorded LGBTQ+ history with a condensed timeline. We do not intend for this timeline to represent a complete history of the LGBTQ+ experience in Charlotte; it is merely a highlight reel of significant moments, people, and places over time. To learn more, please visit the links provided below.

The creation of the Charlotte LGBTQ+ History Timeline would not have been possible without the dedicated, thorough work of Charlotte-based historians and archivists. We would like to specifically acknowledge the efforts Christina Wright, Matt Comer, La Shonda Mims, Joshua Burford, and everyone involved in the continued preservation of the King-Henry-Brockington LGBTQ+ Archive for their contributions to this community history.

1959

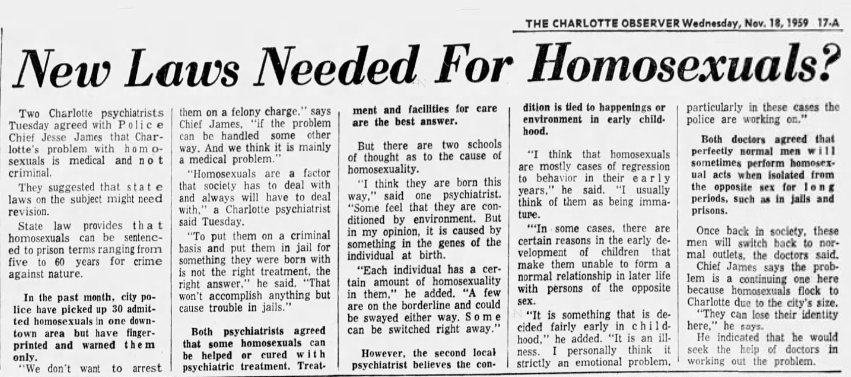

While rumors have circulated about the existence of gay hotspots in Charlotte throughout the 1940s and 50s, an article in the Charlotte Observer from 1959 is some of the earliest evidence we have to confirm the presence of queer space in the “downtown area.” The article notes the apprehension of around 30 gay men.

The Charlotte Observer article via Newspapers.com

1968

Gay bars arrived and quickly disappeared throughout the early/mid 1960s, but 1968 saw the debut of two seminal spaces in Charlotte’s LGBTQ+ history: Oleen’s and The Scorpio Lounge.

Oleen’s initially opened as a straight bar called Xanadu until the owners realized how lucrative being a designated space for the gay community could be. The bar quickly established itself as “The Show Bar of the South” by hosting frequent drag shows and giving a platform for the city’s most legendary drag queens to get their start. It was also a popular space for lesbian women, who could attend performances tailored specifically to them on certain nights. Oleen’s would eventually close in 1997.

The Scorpio Lounge, now simply called The Scorpio, began as a disco club for Charlotte’s gay community. It consistently garnered a diverse crowd in terms of race and gender identity. The club eventually hosted its own drag shows, sparking a local competition between it and Oleen’s. The Scorpio is still open and serving Charlotte’s LGBTQ+ community at 2301 Freedom Drive.

Oleen's via Qnotes (Staff Archives)

1976

Charlotte’s first-ever gay publication, the Charlotte Free Press, debuted a year prior in 1975. However, in 1976 the nation’s longest running lesbian journal, Sinister Wisdom, launched out of an unassuming home in Charlotte’s Country Club Heights neighborhood.

Founded by former UNC Charlotte drama professor Catherine Nicholson and her partner Harriet Ellenberger (Desmoines), Sinister Wisdom only existed in Charlotte for two years before relocating to Lincoln, Nebraska. Even so, the city played a critical role in the journal’s inception. Historian La Shonda Mims links Sinister Wisdom’s origin to the departure of lesbian separatists from the Charlotte Women’s Center.

Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Ellenberger via Sinister Wisdom (Lynda Koolish)

1981

The Charlotte drag scene increased its public presence at the end of the 1970s, culminating in the city’s annual Ms. Renaissance Drag Review drawing 10,000 spectators to the Metrolina Fairgrounds in 1978. Events such as these, as well as popular gay-specific publications like the Charlotte Free Press and Whatever, helped queer visibility reach new heights entering the 1980s. As a result, 1981 was a year of many firsts:

- Queen City Quordinators debuted as a fundraising-focused organization and put together North Carolina’s first-ever Pride events. These events took place over the course of a week on UNC Charlotte’s campus and across various gay bars.

- Friends of Dorothy opens out of an apartment in Dilworth and establishes itself as the city’s first gay bookstore.

- The Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) opens and becomes the first queer affirming church in the “City of Churches.”

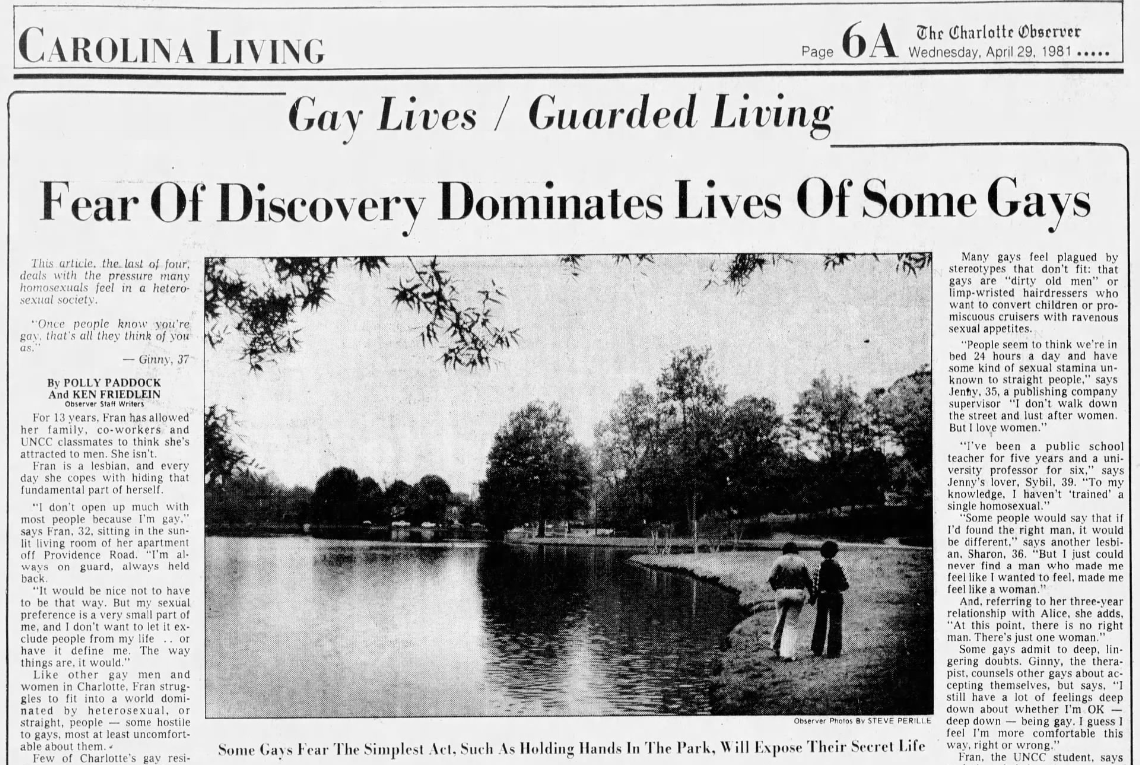

- The Charlotte Observer publishes an article entitled “Gay Lives/Guarded Living” to highlight lived queer experiences throughout the city.

1981 Lesbian & Gay Pride Week via The Sallie Bingham Center at Duke University

Friends of Dorothy bookstore via The King-Henry-Brockington LGBTQ+ Archive

The Charlotte Observer article via Newspapers.com

1983

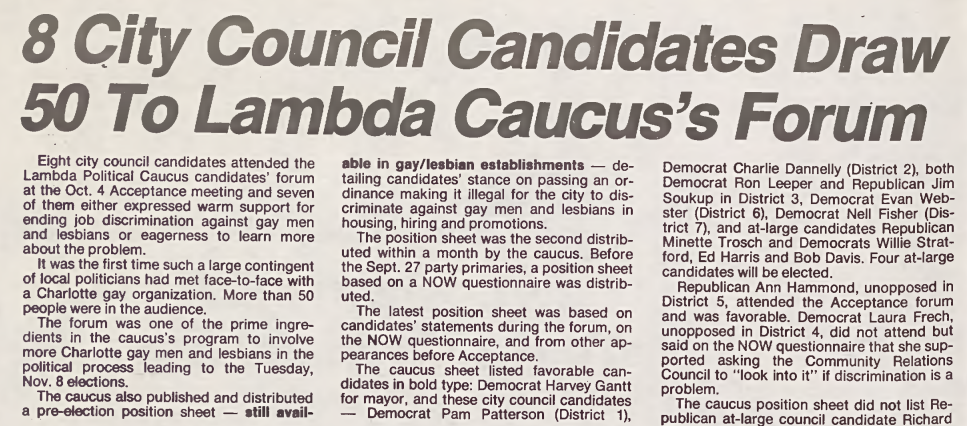

Continuing the LGBTQ+ community’s increased visibility in the 1980s, 1983 saw the beginning of Charlotte’s longest running queer publication, Qnotes. The newspaper began as a humble newsletter of Queen City Quordinators, but it quickly established itself as an important source of information and quality journalism. This year also marked the rebranding of the Gay/Lesbian Caucus to Lambda Political Caucus, which had a significant political presence during the 1983 mayoral election.

Unfortunately, not all major moments in 1983 were positive ones for the LGBTQ+ community. The Charlotte area’s first known case of AIDS appeared in Indian Trail.

Qnotes article via Digital NC

1985

As the community’s attention shifted to combatting the AIDS crisis, six gay men founded Metrolina AIDS Project (MAP). MAP would become one of the city’s most important LGBTQ+ organizations of the 1980s and 90s. They raised funds to support city residents diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, operated a crisis hotline, taught sex education, provided valuable AIDS-related literature, and lobbied local government officials for assistance through the epidemic.

MAP volunteers Kevin Melody and Rick Carswell via Qnotes (Kevin Melody)

1989

A group of LGBTQ+ Charlotteans formed One Voice Chorus, providing an outlet for artistic expression and a sense of community outside of the AIDS crisis. One Voice launched its first season of concerts the following year.

Concert program via One Voice Chorus (Micah Deer)

1994

Charlotte hosted small Pride events every year since 1981, but nothing the city did ever compared to the size and scope of NC Pride. This annual march began in Durham in 1986 but would eventually travel to cities throughout the state in the 1990s. In 1993, a handful of Charlotte’s LGBTQ+ residents formed in a steering committee with the sole intention of bringing NC Pride 1994 to come to the Queen City. The committee placed a bid that included the expansion of the march into an all-out festival, including workshops, vendors, banquets, entertainment, and more.

Charlotte won the bid and hosted the state’s largest Pride celebration in 13 years. Nearly 4,000 people marched through the city’s streets, paving the way more successful LGBTQ+ events to take place in the immediate future.

Archival photo of NC Pride 1994 in Charlotte via the Charlotte Pride History Project

1995

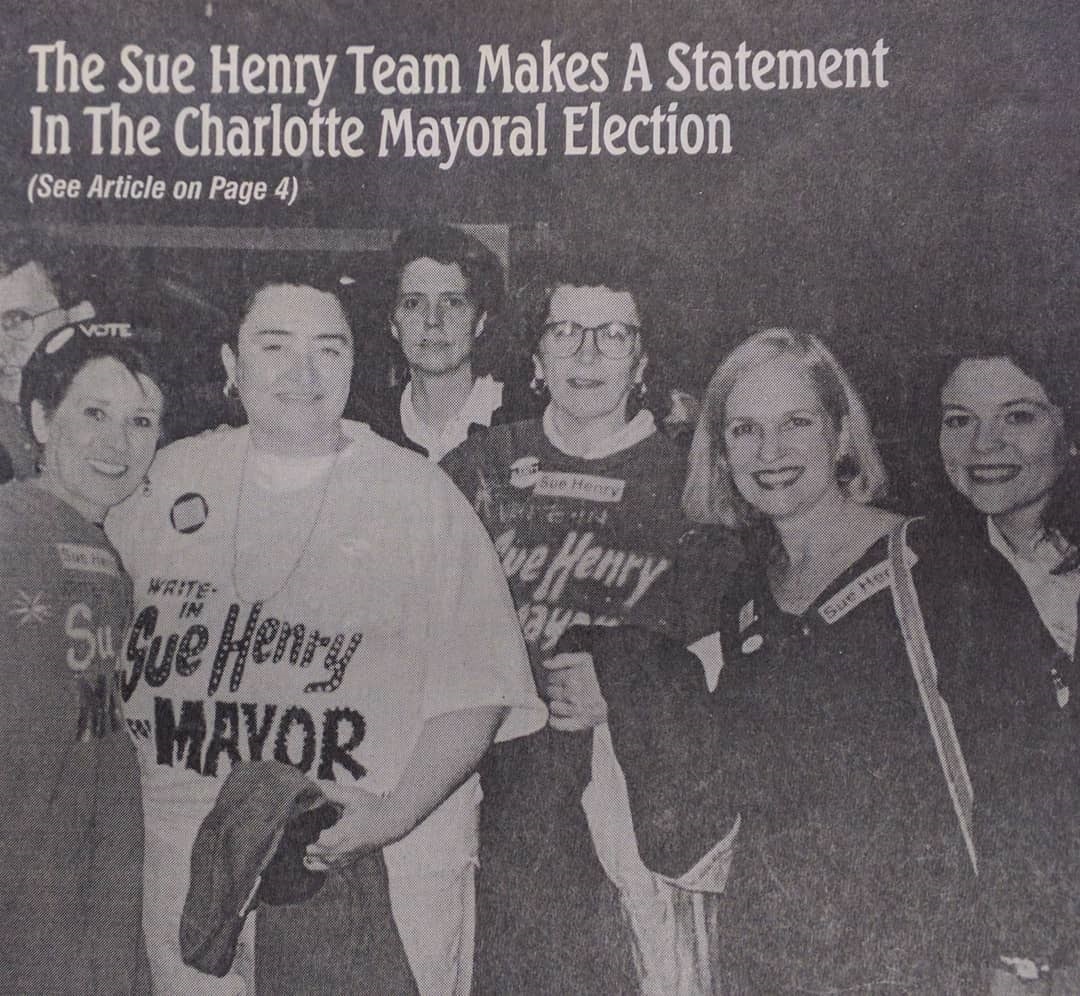

One of the more visible members of the NC Pride 1994 committee and owner of Rising Moon Books & Beyond, Sue Henry, launched a write-in mayoral campaign in 1995—making her the first openly LGBTQ+ candidate to run for Charlotte mayor. She ran against Democratic candidate Beverly Earle and Republican candidate Pat McCrory. The latter won and would later become Governor of North Carolina.

Sue Henry campaign article via the King-Henry-Brockington LGBTQ+ Archive

2000

The LGBTQ+ community of Charlotte craved a boost in visibility and widespread recognition at the turn of the century, which ultimately led to the official founding of Charlotte Pride in 2000. The organization took over annual Pride celebrations from Out Charlotte in 2001 and steadily increased programming each year. Even in the face of rampant anti-LGBTQ+ protests during the organizations first couple of years, Charlotte Pride remained determined and steadfast.

2001 Charlotte Pride materials compiled by the Charlotte Pride History Project

2003

The transgender community of today didn’t really establish itself in Charlotte until the 2010s, but its origins can be traced back to the 2003 formation of TransCarolina by noted LGBTQ+ activist Janice Covington Allison. A few other transgender support groups existed throughout the state in the early 2000s, but Allison felt that they were all missing a necessary social element. The main focus of TransCarolina was bringing transgender individuals out into public spaces. The group traveled all over North Carolina, gaining members from every corner of the state and creating a community that wasn’t content with hiding in the shadows.

Janice Covington Allison via Charlotte LGBTQ+ Oral Histories (UNC Charlotte)

2005

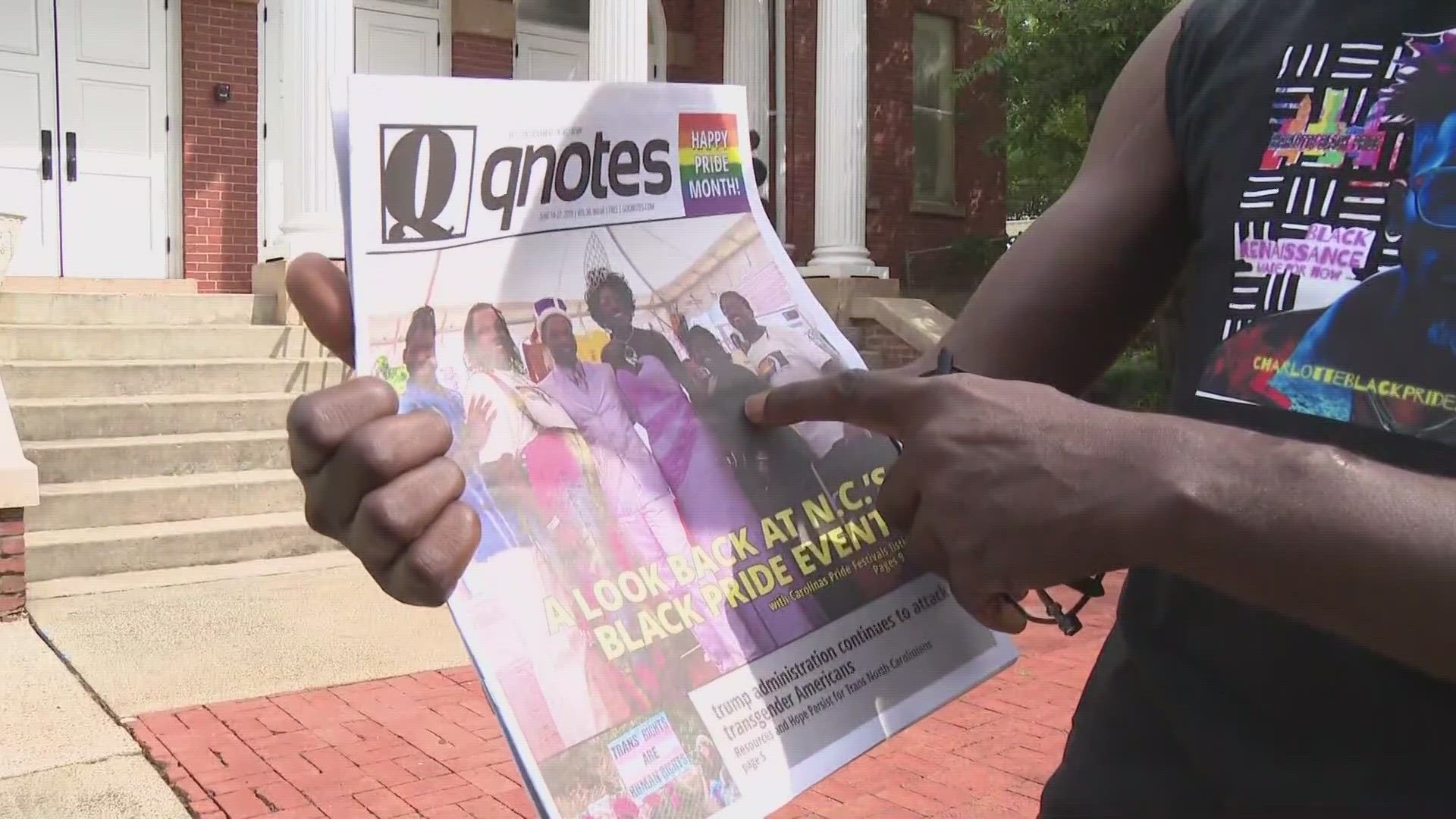

Almost immediately upon his arrival to Charlotte from Miami, Jermaine Nakia Lee noted a significant lack of diversity within the visible queer community. According to his interview for the Charlotte Pride History Project, Lee spent a few years trying to work with Charlotte Pride for a seat at the table, but his concerns remained largely unanswered. This division lead him and Monica Simpson to found Charlotte Black Pride in 2005. The relationship between Charlotte Pride and Charlotte Black Pride has since improved into something more positive and collaborative.

Jermaine Nakia Lee reflects on 18 years of Charlotte Black Pride via WCNC

2011

City Council hopeful LaWana Mayfield makes history by winning the District 3 seat over Ed Toney. With the victory, she became the first openly gay or lesbian elected official in Charlotte. She continued to serve District 3 until 2018. Mayfield would later return to City Council as an at-large representative in 2022.

Since Mayfield’s historic election, other openly LGBTQ+ individuals have proudly served on Charlotte’s City Council, including Al Austin who was elected to represent council District 2 in 2013 and 2015; Billy Maddalon who was appointed by City Council in 2013 to fill the District 1 vacancy; and Danté Anderson who is currently serving her first term as District 1 representative.

Interview with LaWana Mayfield following a Democratic primary victory via WBTV

2012

Janice Covington Allison became more and more active in politics, specifically trans advocacy, as time went on. In 2012, she eventually became the first transgender person from North Carolina to serve as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte.

Allison (middle) at DNC in Charlotte via The Charlotte Observer

2013

Historian and archivist at UNC Charlotte, Joshua Burford, began the LGBTQ+ archive project in 2013 with the intention of collecting and preserving local queer history. Now known as the King-Henry-Brockington LGBTQ+ Archive, the project would eventually become one of the most noteworthy collections of locally sourced LGBTQ+ artifacts in the entire Southeast. The archive is available for public viewing and research at J. Murrey Atkins Library.

Joshua Buford (left), Sue Henry (right) and other at archive naming ceremony via Qnotes.

2014

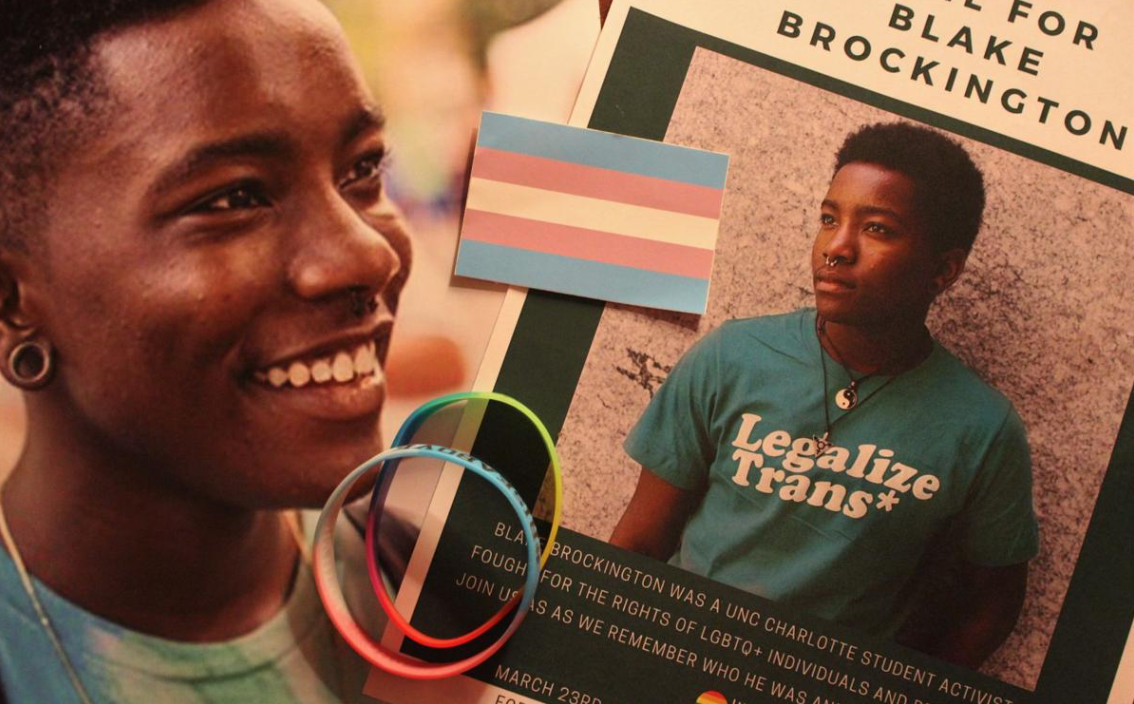

One of the archive’s namesakes, Blake Brockington, rose to national attention in 2014 when he became North Carolina’s first openly transgender high school homecoming king. The East Mecklenburg High School graduate was an active member of the Charlotte community up until his self-inflicted death the following year.

Tribute to Blake Brockington via Niner Times (Mia Shelton)

2016

Charlotte City Council passed a nondiscrimination ordinance (Ordinance 7056) in February 2016. The purpose of the ordinance was to amend previous language in the Charlotte City Code so that it would include marital status, familial status, sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression on its list of characteristics that should not be discriminated against. The inclusion of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression became a sticking point for the ordinance’s opposition.

The following March, N.C. state legislature passed House Bill 2. Publicly known as the “bathroom bill,” HB2 received international attention for its gender-related bathroom restrictions. These restrictions specifically targeted the state’s transgender community with the use of specific language regarding biological sex as “stated on a person’s birth certificate.” Controversy surrounding the adoption of the bill had a significant impact on the state’s economy; for example, Charlotte lost its opportunity to host the 2017 NBA All-Star Game as a result of the law.

2016 LGBTQ+ rights rally in Charlotte via the New York Times (Travis Dove)

2021

The repeal of HB2 happened over the course of a few years, but it was fully removed from North Carolina law in 2020. The following year, the City of Charlotte once again amended its Human Relations Ordinance to further extend protections to LGBTQ+ residents.

Local support for nondiscrimination ordinance via Spectrum News

IMPORTANT SOURCES